The Argument for God from Experience: Are Mystical Experiences Authoritative?

- cbahl2000

- Sep 16, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 29, 2025

"It is vain for rationalism to grumble about this. If the mystical truth that comes to a man proves to be a force that he can live by, what mandate have we of the majority to order him to live any other way." (1)

The Experiential Argument for God's Existence

As a brief review, here is my argument to date:

Premise 1: Human beings have experiences that evoke a profound sense of dependence, awe, and transcendence (what Schleiermacher calls the feeling of absolute dependence).

Premise 2: These experiences are epistemically significant. Importantly, they constitute non-propositional knowledge.

Premise 3: The depth and universality of these feelings point toward a reality that is non-contingent.

Conclusion: Therefore, the experiences of dependence, awe, and transcendence are not merely psychological but ontological. They invite interpretation of the self as in-relation-to an Ultimate (what theology names God).

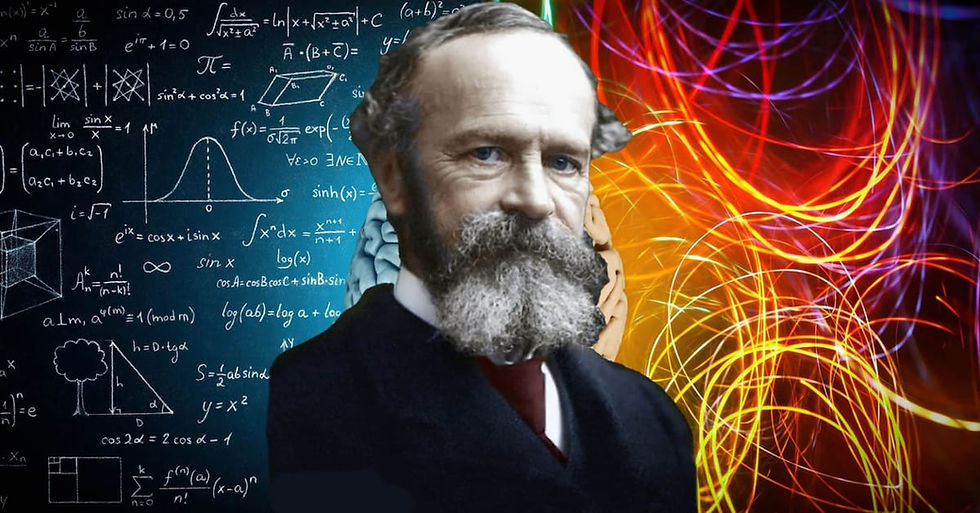

I have previously focused on Premises 1 and 2. In my most recent entry on the topic, I turned to a defense of Premise 3, utilizing the research of William James to help show religious experiences not only share the characteristic of commonality, but also depth.

Today, I continue with the work of William James to explore the question of whether religious experience can point to a non-contingent reality.

Specifically, I will seek to answer the question, "Can the feelings of dependence, awe, and transcendence be taken to be authoritative?"

The Question of Authority

In "The Varieties of Religious Experience," after James opines on several, varying examples of mystical experience, he turns to the question of authority. By asking if mystical experiences are authoritative, James is seeking to explore whether or not they are (1) credible, (2) an accurate portrayal of reality, and (3) contextually relevant.

James' response, worth considering, is broken down into three parts:

In what way are mystical states authoritative?

Who is bound by such authority?

What are the larger implications for other sources of authority?

In What Way are Mystical States Authoritative?

James’ answer is that mystical experiences can and should be considered authoritative to those who have them.

Mystical experiences (these ineffable, noetic, transient states) seem real to the experiencers and often have genuine and lasting impacts in their lives.

We can freely question such experiences. As James states, "We can throw them in prison or a madhouse..." but we cannot change their minds.

In fact, James points out to refute these experiences, "mocks our utmost efforts, as to matters of fact, and in point of logic it absolutely escapes our jurisdiction. Our own more 'rational' beliefs are based on evidence exactly similar in nature to that which mystics quote for theirs."

Indeed, the five senses assure us of certain facts. But mystical experiences are also perceptual in nature. If the authority of one is able to be questioned, the authority of all must be. This is an observation which undergirds Alston's epistemological argument.

Who is Bound by Such Authority?

James is clear in his distinction: mystical experience should be considered authoritative for the experiencer, but mystical experience is not required to be authoritative for those who stand outside it.

Blind acceptance is not a mandate for those who have no such experience.

Indeed, James acknowledges there are many who may never have mystical experience, there are those who may have non-religious mystical experiences, and there are those whose mystical experiences include content which may seem contradictory to others.

It is never a good idea to approach truth claims uncritically. Those engendered through religious mystical experience are not an exception.

What are the Implications for Other Sources of Authority?

The above, however, should serve as no indication that James sees religious mystical experience as epistemically insignificant.

For him, these experiences, "break down the authority of the non-mystical or rationalistic consciousness, based on the understanding of the senses alone. They show it to be only one kind of consciousness."

Indeed, religious mystical experiences open up the possibilities to other, less explored or perceptually obvious truths.

They are ingredients in the overall cosmic soup of information humanity perceives and the denial of their epistemic importance makes the soup no less flavorful to the receptive palette.

The utility of visual acuity is not denied by the blind. In the same way, James entreats those who never experience mystical perception to acknowledge the validity, as a truth source, of those who do.

For James, such experiences "point in directions to which the religious sentiments of even non-mystical men incline."

Bringing it Together

Over my blog posts so far arguing for the existence of God from the experience of humanity (eight of them to date) I have sought to establish three key premises:

Premise 1: Human beings have experiences that evoke a profound sense of dependence, awe, and transcendence (what Schleiermacher calls the feeling of absolute dependence).

Premise 2: These experiences are epistemically significant. Importantly, they constitute non-propositional knowledge.

Premise 3: The depth and universality of these feelings point toward a reality that is non-contingent.

I will leave the conclusion to the reader of whether or not I have been successful in my venture.

If my argument is sound, the conclusion should follow that, "Therefore, the experiences of dependence, awe, and transcendence are not merely psychological but ontological. They invite interpretation of the self as in-relation-to an Ultimate (what theology names God)."

In my next post, I will attempt to tie together these ideas in support of this conclusion.

(1) William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience. (New York: The Modern Library, 1902), 135.

Comments